King Street Pilot Lie (Part 3 #DataMatters): Jennifer Keesmaat, et al.; The Pilot Lie; And Other Myths

It was hearing Matt Galloway describe the King Street Pilot as “wildly successful” on a Wednesday morning that initiated the third installment of the King Street Pilot Lie. CBC Radio is the go-to for many Canadians and the home of the national broadcast; with countrywide berth, the power and influence that they are bestowed to spoon-feed public knowledge invariably extends to public perception. And, in this case, to inform listeners that the pilot is wildly successful is what many people now believe to be true. By saying so, Matt Galloway was also transparent in his alignment with CBC’s newly hired personality, Jennifer Keesmaat, an expert on urban issues and all-things public transportation. Keesmaat, and her long list of devotees on Twitter, many of whom seemingly accept her tweets as scripture, are consistently highlighting the successes of the pilot; however, with mounting evidence that contradicts much of this praise, more and more of what’s being touted comes across as confirmation bias as opposed to objective reasoning.

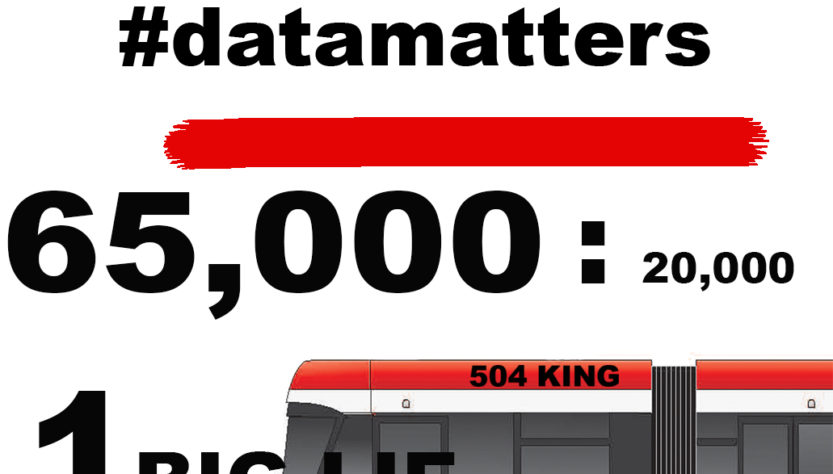

Let us accurately represent data to all, for as Keesmaat claims, “#datamatters”.

It appears Torontonians missed a clear point (from previous articles here and here) that members of the City misled them with a 3:1 transit-to-vehicle ratio regarding the King Street Pilot Project. By dint of social media and analytics, it’s evident the articles are being noticed in the tens of thousands, and the crescendo has now bottomed. Efforts to clarify a serious discrepancy in the pilot data were never made by key figures, including Mayor John Tory, Councillor Joe Cressy, and former Chief Planner for the City of Toronto, Jennifer Keesmaat, who was instrumental in the pilot’s creation. The discrepancy was likely never met with any scrutiny as it was so subtle in its imbalanced comparison that for the sake of a legacy project it could probably go unnoticed. This goes beyond the innocuous phrase of “fudging numbers”—the equivalent of a mere rounding error of sorts. This was a clear perceptual pivot, one that clearly manipulated those in the media, then buoyed by embroidered tweets and soundbites that exalted the project from its launch. And while many citizens continued to graze on the pastures of ignorance (many of whom still continue to purport the glories of the project), it gradually became less about the merits of a pilot project and more about a tool that polarized in a political battleground: those for the pilot generally align themselves with the political Left, while those who oppose it, align to the Right—an exceedingly Manichean, reductionist problem in our culture today. More importantly, those for the pilot recurrently cried about an injustice, referring to the claims that the unmet needs of 65,000 transit riders were the result of the indulgent car drivers who numbered at just a mere 20,000. The uninitiated then took a side, but they were completely misinformed by those figures (see articles above for more exact data). It’s difficult to blame the public, or even the media, as they took the proposal and data presented by the GM of Transportation Services and Chief Planner and Executive Director of City Planning, as accurate. In the proposal and in a June 2017 Study, the primary concern was that “King Street moves 65,000 transit riders every weekday, compared to only 20,000 vehicles” which was enough to compel Toronto City Council. The comparison was a fraudulent claim since 65,000 represented the entire 14 kms of road along the 504 King line, while 20,000 vehicles represented the pilot zone, but more specifically, that figure represented a total of vehicles at one intersection which was used as a sum total for the zone. So, the question then becomes, did the accused parties know that this was a false comparison, deliberately crafted as such to compel council to move ahead with a project that cost $1.5 million of taxpayers’ dollars towards a project that lacked in-depth research and data, or were they completely inept in understanding that the ratio never should have been made which was then unethically utilized to mislead and sway council? Are any of these scenarios acceptable? At the very least, as a collective, Torontonians from both the political Left and Right can agree, that as citizens they can demand transparency and incorruptible integrity from those taking public office.

“OOPS!” THE CITY’S MISSING SPREADSHEET / DATA

The data presented in the article The King Street Pilot Lie (Part 2): The “Integrity” Behind The Numbers, includes totals for vehicle counts that were provided by the City on their site, and it was provided in response to those inquiring about the King Street Pilot project. However, since the release of the above articles, the cordon data spreadsheet has been removed from its link on the City’s site, and away from inquiring minds. The timing couldn’t be more awkward, and the City attributes the misplacement of the spreadsheet, and all of its crucial contents to back-end maintenance, while other data, including illustrations of how the pilot is currently functioning, is still readily available. It’s been months since this link has gone missing, however, for inquiring minds a copy is provided here.

Recognized and heavily referenced for her opinions on transit, Keesmaat is buttressed by support from her bedrock of 70K+ Twitter followers. Analyzing and unpacking the information, tone, and suggestive claims made by Jennifer Keesmaat:

Former Chief City Planner and now resident expert at the CBC, Jennifer Keesmaat, points out by way of social media, that “#datamatters” (right). Certainly, data should matter, and it matters even more for all those willing to look at all the data. It’s also a growing curiosity that many seem to believe that the current King Street pilot numbers are more important than whether members of municipality deliberately misled to sell the public and Council on the project, while their misalignment of data is now somehow irrelevant. Where are the principal players (Coun. Joe Cressy; Mayor John Tory; Jennifer Keesmaat, et al.) in responding to the pre-pilot data? If data matters, it would seem relevant to address the 3:1 ratio. More importantly, it would seem imperative that mainstream media investigate, however, a rogue restaurateur with a profane ice sculpture seems to grab the headlines. If data matters, it would seem relevant then for resident experts at the CBC or elsewhere to address the 3:1 ratio and its fraudulent comparison.

Also, the current dashboard numbers carry little weight in the face of the pilot’s dubious launch. Even still, dashboard infographics and their highlights, have been selective and embellished–particularly in light of experts suggesting that improvements have been at best modest by comparison. It should be no surprise that when diverting vehicle traffic, transit commute times would improve to some degree, but there’s little to celebrate here in terms of improvement or intellectual reach as far as data analysis goes.

If a pilot were created whereby streetcar thoroughfare was banned inside a zone, the number of all-day car passengers would also see “improvements”, with commute times also being “successfully” decreased, all of which could be distributed through easy-to-swallow illustrations from a dashboard, condensed into ready-to-use tweets and clickbait declaratives. More importantly, since vehicle passengers outnumbered those on the 504 transit route in an all-day count before the pilot launched, why weren’t vehicles prioritized for a pilot? What are the counts on Dundas Street now that streetcars have been temporarily replaced by buses, and what are their commute times now that the parade of impeding, lumbering streetcars no longer cluster the line? Many commuters have expressed that with buses now operating on Dundas, their commute times have been significantly decreased, while vehicle passengers are making similar claims. Streetcars look more and more the culprit behind Toronto traffic, and yet the City finds it simpler to alter the City for the streetcar rather than alter the mode of public transit. A healthy public transit and traffic solution seems to resemble something found in larger cosmopolitan cities: subways and buses rather than streetcars—if any are ever present—make up a larger part of this equation.

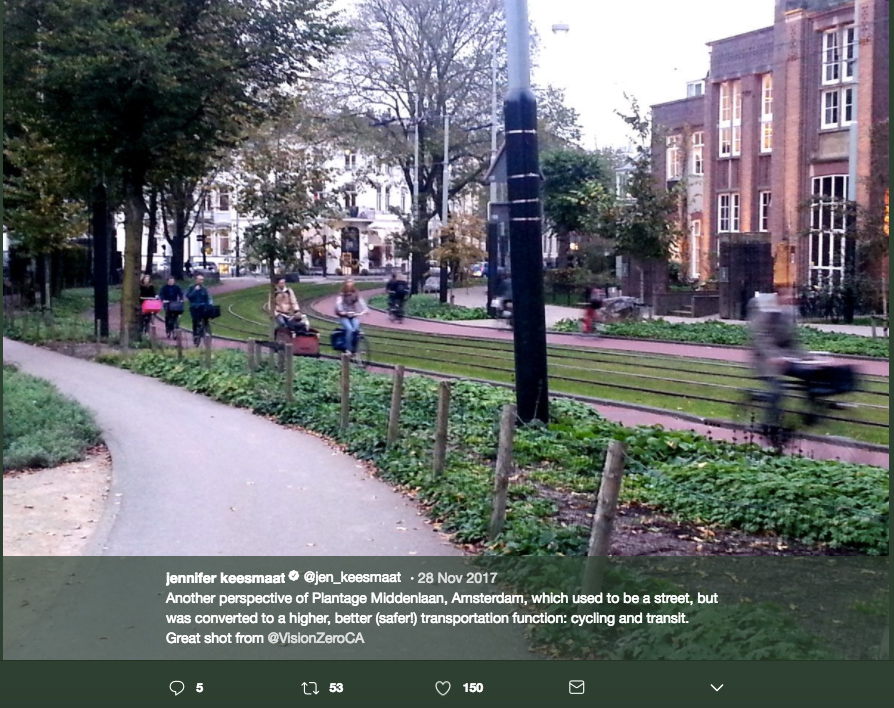

27 Nov 2017 (left). This tweet illustrates a transparent attempt by Keesmaat to justify projects like the King Street Pilot (and a seemingly growing obsession to limit or abolish private vehicle access); but while the visual is a European ideal in its tableau—garnering an enthusiastic 1.4K likes—it fails to illustrate an important message: that changes to urban landscapes like this are considered and made possible mainly because the collateral damage to the area would be negligible. Moreover, the lack of density in this corridor, particularly with the amount of exposed sky, should tip any observer. Note that there are as many trees as there are residential properties, and the lack of high rise buildings—unlike the King Street Pilot zone—suggests that vehicle traffic in the area would not be impacted as it would in denser, higher trafficked areas; allowing for these changes that are more pedestrian-friendly to occur with little or no consequence.

28 Nov 2017 (right). Another angle/extension of the previous photograph of Plantage Middenlaan: The removal of the car lane is made possible here due to several factors, some of which include, density per square mile, and what infrastructure is already in place alleviates any traffic-related qualms. Note the lack of skyscrapers in the photo (other photos like these here and here, also show the area’s lack of density). Unlike what you would find along the King Street Pilot zone, the area is scant of human activity, the kind you’d find on King Street in Toronto. The key difference is that Plantage Middenlaan is not nearly as dense as parts of downtown Toronto; there’s nothing remarkable about this “pedestrian friendly” conversion, however, it only makes complete sense there—in Plantage Middenlaan, Amsterdam. Toronto is not Amsterdam, and city planners should understand inherent truths before exercising fantastical aspirations, but also consult experts and data on their feasibility and objective outcomes.

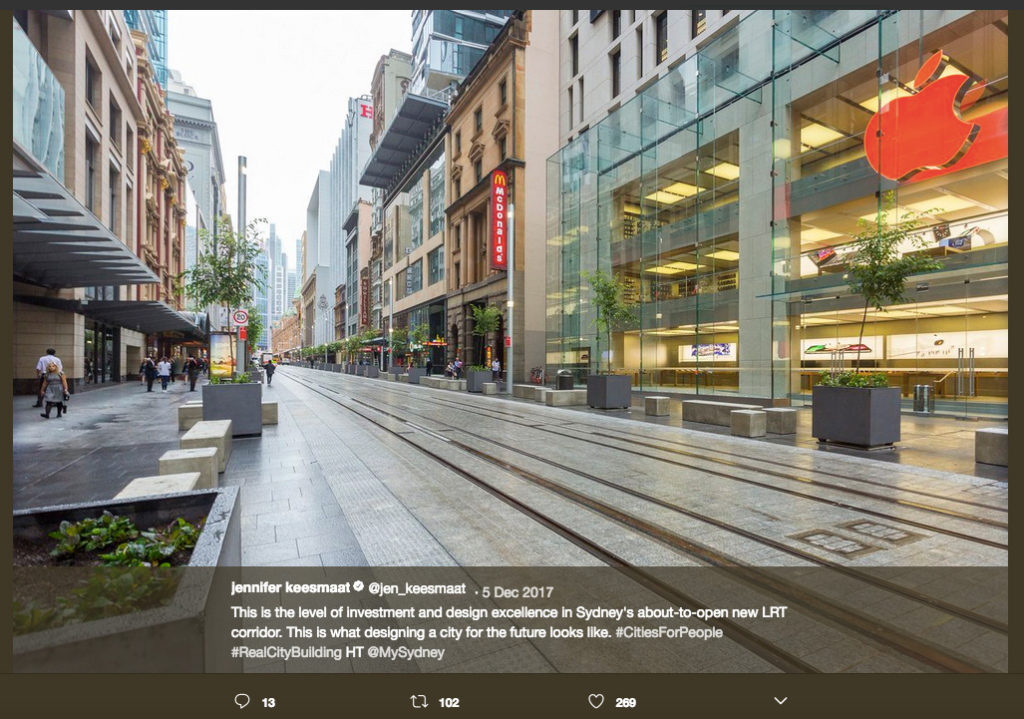

5 Dec 2017 (left). This is one tweet/visual by Keesmaat that comes close to making a reasonable comparison for justifying a project similar to the King Street Pilot; however, this is part of a 12 km $2 billion dollar project, where much of the streetcar is designated away from main streets and car thoroughfare in Sydney, while access remains mostly the same: “approximately 60% of George St. will still be open to vehicles, with one lane of traffic maintained in each direction alongside the light rail tracks. East-west road corridors will remain open for motorists traveling across town and access to properties and businesses will be maintained. A 1 km [only] pedestrian zone will be created…”

The differences between the King Street Pilot Project and the one in Sydney are significant, particularly with regards to the number of businesses affected. The project at this end, which blocks car thoroughfare for one kilometre—although it appears taxis and commercial trucks will still have access inside this stretch of George Street—is something suited for Toronto’s immediate financial district (equivalent to Sydney’s CBD) and not the remainder of the King West area. A 1 km ban on car thoroughfare would be a less disruptive decision to have implemented as part of a pilot project, as opposed to the 2.6 kms that was taken away with the King Street Pilot, which diverts private vehicles and customers away from the area.

SPEED LIMITS and VEHICLE VIOLENCE

Keesmaat’s frequent guest spots on CBC Radio include a recent morning stop (Wednesday, April 25th), soon after the tragic incident that involved a van and ten dead pedestrians in northern Toronto. The discussion focused partly on speed limits inside busy cities and the benefits to lowering them to prevent or limit the loss of pedestrian life due to vehicular accidents. It’s a wonder what correlation can be made between a tragic incident that involved a deranged individual deliberately plowing into pedestrians (i.e. an extremely rare one-off where an individual consciously disregarded speed limits, lanes and human life), and lowering speed limits in a city. As Keesmaat herself acknowledges the incident to be more “strategic” and isn’t something to be considered as “a widespread risk”, the timing of this broadcast then becomes questionable or even transparent in that the tragedy is an awkward pretext to push an agenda that includes the Vision Zero mandate mentioned in the broadcast. Rather than discussing bollards and lowering speed limits, perhaps the episode should have stressed the mental health needs in Toronto, the ever-increasing strain on public resources and the lack of resources needed to combat what should have been the takeaway from Monday’s incident—mental health.

Nonetheless, the tragedy occasioned a discussion on CBC Radio to opportune a moment to confer on the issue of altering speed limits; however, to say that the unfortunate individuals in the tragedy couldn’t react in time to a speeding van with a disturbed driver inside in order to highlight a need to lower speed limits across the city, and to inform the radio listeners to this plea, is simply taking advantage of a tragedy at its worst and is misaligned in its logic at its best. The episode also included Alan Bell, president of Globe Risk International, who somewhat balanced the three-guest panel that also included Claire Weisz, who cited an example in New York regarding bike lanes to which Keesmaat suggests is part of “our priorities” and what “democracy is about”.

It is a peculiar thing the way the word democracy is used these days, an often seemingly romantic notion that sways from the rule of the majority one day, to ruling over the majority the next. That said, let us once again delve into the King Street Pilot, because somewhere, as Jennifer Keesmaat suggests, ‘democracy’ is at work.

WHILE THE PILOT CONTINUES ITS TRIAL, THE BREACH IN ETHICS REGARDING ITS LAUNCH IS BEING SUPERSEDED BY THE PRO-PILOT CONTINGENT

Urban issues columnist for the Toronto Star, Christopher Hume, also gets in on the King Street Pilot debate. With authoritarian zeal in an opinion piece written January 16th, it was headlined, “Whether you like it or not, the King Street transit changes are here to stay.” One can almost hear the defiant foot stomp at the end of ‘whether you like it or not’; sounding more like a tyrannical rallying cry, Christopher has since deleted the headline online, revising it to “Why the King St. transit changes are here to stay”. [Hume also falsely acknowledged that 65,000 transit riders are being impacted when they’re not; see previous articles for pre-pilot data, as a fraction of the 65,000 ever traversed through the pilot zone]. However, what also stands out from Hume’s article is a quote from Coun. Joe Cressy:

“We have to redesign our streets to move people not cars. Unless we can get in and out of downtown quickly, we’re screwed. When downtown does well, the city does well. Travel times have improved on King by up to 15 to 20 minutes per trip.” — Councillor Joe Cressy

Who exactly is Cressy talking about when he refers to those getting in and out of downtown quickly? The often vehicle-dependent suburbanite or those privileged to afford living inside or near the pilot zone? Is this a project for all Torontonians, or just the prosperous, white collar pockets of Liberty Village and the Distillery? Why doesn’t the project stretch into Parkdale and Broadview? Moving “people not cars”? Are cars now not moving people?

It’s often said that it can no longer be assumed that inner-city roads can continue to take an influx of vehicles and that “we” have to encourage drivers to abandon their cars for public transit alternatives. But this would also inherently create an unmanageable influx of commuters toward a public transit system that can barely handle its current influx of urban dwellers at peak hours. Current data shows that improvements to travel times, particularly during peak hours—the hours claimed to be the busiest and the primary reason for the pilot—are marginal at best. An increase in ridership in the short term also proves little other than the fact that TTC temporarily increases its revenue; take for instance, when the right-of-way 510 Spadina was built, it saw a steady, impressive increase of an additional 10,000 riders in 2011, but by 2014 it dropped to 2005 levels; an incredible failure considering the growth in population density during this period. It becomes a meaningless statistic because despite the right-of-way, the travel times weren’t significantly reduced, and the same could potentially occur with the 504 line. With increased density coupled with additional streetcars, anticipate travel times to worsen. Perhaps, Cressy’s “up to” sell of travel times should be reserved for the riders who travel outside of peak hours who are significantly smaller in number. Note, that pre-pilot data shows vehicle occupancy exceeding transit ridership by a considerable margin along the 504 King route in an all-day count. Taking this into consideration—negligible reduced travel times for the majority during peak hours while thousands of vehicles and businesses have been negatively impacted—all of this, to come back to Keesmaat’s sentiment, doesn’t sound very “democratic”. So-called democracy is hard to see here, particularly when members of the City found it necessary to launch a pilot project on an erroneous comparison—a 3:1 transit-to-vehicle ratio that never existed.

Where’s the official inquiry? Where are the principal players in addressing the erroneous 3:1 claim on CBC Radio? Why doesn’t someone ask the City to explain the 20,000 vehicle count in detail?

WHAT WORKS IN NEW YORK MIGHT WORK FOR TORONTO, OR IT MIGHT NOT. IT’S NOT A GIVEN, AND TO USE NEW YORK’S SUCCESS FOR ITS TRANSPORTATION AND PUBLIC SPACES INITIATIVES, WHICH DIFFERS COMPLETELY IN POPULATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE TO THAT OF TORONTO, IS MISAPPROPRIATION OF DATA AND CASE STUDIES, REQUIRING FURTHER CRITICAL, IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS.

There seems to be an infinite amount of data regarding urban transportation that can be skewed endlessly as a means to manipulate public perception. Many observations are mere promotional engines for all that’s feel-good and healthy in contemporary urban planning, promoting transportation decisions that on the surface benefit a majority while striking at the always “evil” private vehicle. The oversimplification of reducing vehicles to objects that terrorize, or to exclaim that as a “mother with children” one feels unsafe walking the streets of Toronto, speaks more to paranoia and scaremongering than it does to making urban planning decisions; because those who aren’t mothers of vulnerable children, are also concerned with safety. Many urban planners cite European ideals for public transit and public spaces initiatives, but the obvious problem is that Toronto is not Berlin, or Paris, and while a few planners might want to simply download European visions onto Toronto’s landscape, the process is a lot more complicated than wishful tweets attached with computer-generated renderings from urban design magazines, or praising photos of streetcars rolling through quaint European towns.

To be clear, many also argue streetcars are outmoded, but this is far from true. Streetcars make sense under specific circumstances, in particular that they are a mode of transportation where population density is low, for example, Ottawa makes for an ideal location; the O-Train is set to open later this year, a plan as it currently stands makes sense, like it does in low density areas of Amsterdam or Zurich. Portland has also seen remarkable success with is streetcar, but again, the city’s modest population density allows for it to be a success. Ergo, perhaps it’s time that a discussion on CBC Radio take place to discuss whether or not streetcars in Toronto should be replaced on certain routes, and whether the contract with Bombardier was shortsighted, and whether aspects of SmartTrack, which includes new light rail projects, is also setting the City backwards. What are the costs associated with new LRTs and wouldn’t they be best deferred to the DRL? Buses along Dundas have temporarily replaced streetcars there, and many commuters are exclaiming reduced travel times and greater reliability. Do we still need streetcars along Dundas or are buses preferable, placing value on speed over comfort? An article from CityLab titled “Enough With The Streetcars Already” suggests that an obsession with streetcars might be deluding city planners with their grand visions, encouraging change for other alternatives. These are questions that aren’t being posed in Toronto, but proposals are accepted quite readily in for projects that could be looking to the past, when Toronto could be looking to the future.

At a time when headlines proclaim that “Uber hopes to have self-driving cars in service in 18 months” the world of monumental urban change is upon us. Utopian ideals are around the corner and it will start sooner with autonomous vehicles than it will with ROW streetcars. In the future, there’s a chance you’re more likely to see less of public transit than you will more of it. A recent CityLab article by Jarrett Walker titled “Should Transit Agencies Panic?” misses the point entirely; Walker is one man up against “many” who are spelling the “doom” of public transit. Transit isn’t going away, but it and/or its ridership will shrink over time; the TTC has already seen it for a number of years–this is particularly remarkable when you consider Toronto’s recent density transformation.

The possibility of automated buses aside, if a competing automated service comes about that picks up customers at their door, at or near equal cost to public transit, with marginal waiting time, this will disrupt public transportation by more than the estimated 5% that it’s assumed it is now by the likes of Uber. In a CBC radio interview with Matt Galloway, TTC Chair Josh Colle described an idea implemented in Chicago to help fund its public transit system; the idea essentially taxes Uber 15 cents for every ride which then goes to promote public transit initiatives. This sounds incredibly desperate and it implicates ride-sharing as a primary culprit to ridership losses, now and in the future, and perhaps why projects like the King Street pilot are in part initiated––to increase ridership and revenues when overall ridership is falling.* But the question then becomes, why stop at taxing Uber? Why don’t we tax Apple 15 cents for every product and service they sell in Canada and frivolously hand it over to BlackBerry because Apple has disrupted the cellphone market? *See also: “TTC approves ridership growth strategy” — Toronto Star; “TTC ridership is lower than expected…” —Toronto Star.

Some of the writing is already on the wall, and this creates a huge impending crisis for the TTC in the coming years; what the TTC hasn’t fully acknowledged openly, is that the loss in overall ridership over the past 4-5 years has a lot to do with Uber and programs like it. At peak hours, the King Street Pilot has seen negligible improvement in commute times, minuscule numbers considering how much was done to open its pathway. And these times will not likely improve, in fact they may worsen with an increase in ridership, and density in the area. Adding more streetcars will shorten the commute savings as each will have to stop and pick up and unload at each stop; the procession can only go at a certain maximum speed at peak hours, because unlike buses, streetcars have to wait in line like the rider waiting for the next streetcar. Condo dwellers inside Toronto’s core often take Uber or some other ride-sharing program, a new generation of stay-at-home or part-time workers who’d rather the convenience of being privately chauffeured and pay a slight premium than get crammed into a streeetcar. This translates to a new generation less likely to take public transit and more likely to walk, cycle, Uber, or use car sharing programs (CAR2GO, ZipCar).

It’s somewhat surprising that not a single broadsheet journalist has picked up the story that discredits the King Street Pilot Project at its inception.

To borrow from that CityLab article titled “Enough With The Streetcars Already“, Laura Bliss writes “…what is possible to build is more important than what should be built”; this also mirrors a famous line executed brilliantly by actor Jeff Goldblum, that experts “were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should”. It’s perhaps the urgency and the extent of change which ushered in an almost immediate resultant void of pedestrians and vehicle traffic into the King Street Pilot area—negligible improvements to commute times, and disgruntled business owners—that has arguably stripped the project of its credibility. Perhaps, an incremental approach to alleviate congestion in the pilot zone would have been best (e.g. enforcing no left turns throughout and/or make changes for peak hours). What’s troubling with regards to the state of urban planning, is that a few bureaucratic voices can overpower the voices of many or sway them to parrot their utterances. By virtue of title and status, we exalt those deemed experts instead of questioning their conclusions and uphold those in positions of power to objective scrutiny; not just for fair outcomes or for judicious spending of tax dollars, but for the integrity of journalism. Had someone in the media merely questioned what portion of King represented 65,000 transit riders and what portion of King represented 20,000 private vehicles in the pre-pilot data, a glaring falsehood would have been immediately exposed in its fraudulent comparison. In an article published in the Globe and Mail titled, “What has gone wrong since the ‘golden age’ of Toronto transit” author Stephen Wickens interviewed a few of Toronto’s now éminence grise on the general state of public transit and urban planning. Transit expert Dr. Richard Soberman was quoted as saying, “transportation has become a bullshit field…[where a] transportation planner can say anything” then going on to say “there’s no downside other than you waste public funds”. Tongue in cheek aside, experts of all stripes, even those who have tenured public office have to embrace criticism of their ideas, even if the only downside is a “waste of public funds,” for like the pilot, they’re to be upheld to scrutiny—all in the name of democracy.