Toronto’s King Street Pilot Project: Less King, More Pauper

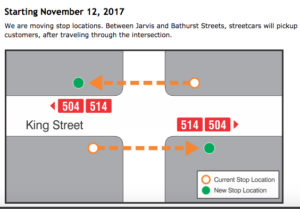

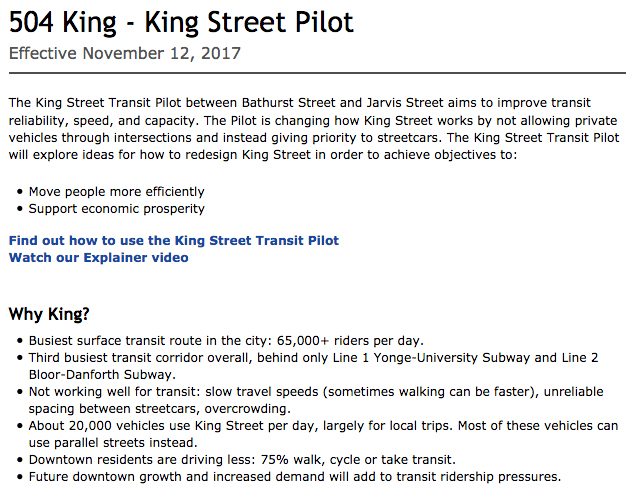

On November 12, 2017, City Officials in Toronto agreed to launch the King Street Pilot Project in hopes to improve the commute for transit riders along an above-ground route deemed the busiest for streetcars by the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC). The plan was to divert all vehicle traffic inside the busiest and most congested 3 km portion of King Street where one can find the Toronto Stock Exchange, the heart of its entertainment district, stretches of trendy high-end clubs, and popular food and beverage establishments. The project prevents private vehicle thoroughfare along the stretch, and would invariably have benefits to commute times for transit riders. For transit users, and by much of the media, it was immediately hailed a success, but for most of the businesses along the stretch, it’s been nothing short of disastrous. All of this has ignited enmity among drivers, business owners and transit riders who are protective of the project. In the midst of this fray, what has slipped past the purview of most are the reasons for why the pilot was launched in the first place. It’s been stated by the City and the TTC that King wasn’t “working” and that 65K transit riders traverse along the 504 line as opposed to only 20K vehicles; suggesting a 3:1 ratio in favour of public transit as grounds for the launch. However, no one has thoroughly questioned the numbers. By impressing onto the public that transit riders exceed private vehicle passengers by a multiple of three, it’s apparent that the pilot was launched by misleading with data that on closer inspection is disingenuously skewed to favour public transit over vehicles (and local businesses).

It’s difficult for many to see the objective truth as many see transit riders exceeding vehicle traffic in this area. This has swayed public opinion where empathy for the current losses in the neighborhood is non-existent. Many see the needs of a majority being met, while businesses and their supposed rich owners (and wealthy customers) be damned. Perhaps all of this would be fair, if it were true. Basically, this should be an issue of transparency and holding municipality accountable for their decisions and not about alleged improvements or ways to “animate” a project that is now seeing a legion of detractors. The project has diverted an estimated 20,000 vehicles (the City’s estimate) to nearby side roads and parallel streets, where an increase in vehicular traffic would of course be inevitable. For most, this would seem an obvious consequence, one that TTC and City Officials deemed inconsequential for the prospects of the 504 King line. Whether this was a lack of knowledge in the area of physics is unknown, but surely, the experts must have known there would be consequences in this regard. Surely, they must have known that you cannot force drivers to simply abandon their choice of transport for public transit by inconveniencing them. In addition, the former Chief City Planner, Jennifer Keesmaat, who is behind the pilot, suggests quite strongly that vehicles terrorize and are an unsustainable form of transport. Whether you agree with Jennifer or however you see the pilot as it stands currently, one thing is for certain: the overall consensus among City Officials is for many to simply “adapt” irrespective of the consequences. Mayor John Tory quite stubbornly has suggested that since pedestrians often walk faster than the streetcars at rush hour, the pilot has to be executed and enforced as a result, but this over-simplified perspective completely excludes the fact that those same pedestrians are also walking faster than non-transit vehicles that are also stagnant at peak hours.

One should have an aversion to projects that are exercised with autocratic dexterity, even ones under the auspice of benefiting a majority; however, the King Street Pilot does not benefit all or the majority, more specifically the idea of assisting those deemed less fortunate who cannot afford the costs of owning and operating a vehicle. The idea that the pilot is benefiting the “little guy” is a fallacy. It’s an idea that shelters the City and the TTC from criticism for launching a project that is flawed, but mostly for deceptively misleading with data that suggests more transit passengers traverse through the pilot zone than vehicle passengers as justification for the project. In addition, the pilot is in a zone that benefits many white collar citizens who live in areas that are out of reach to many citizens financially, where expensive condos or their high rents exclude a good majority of citizens, especially those dependent on public transit; this includes Liberty Village and the Distillery District as key start and end points. The main concern for any citizen should be whether or not this pilot was launched on false pretenses and whether Municipality has been honest and transparent; that is, whether any part of the reasoning for the pilot was misleading—the data and the representation of that data—as a way to fulfill a pro-streetcar agenda.

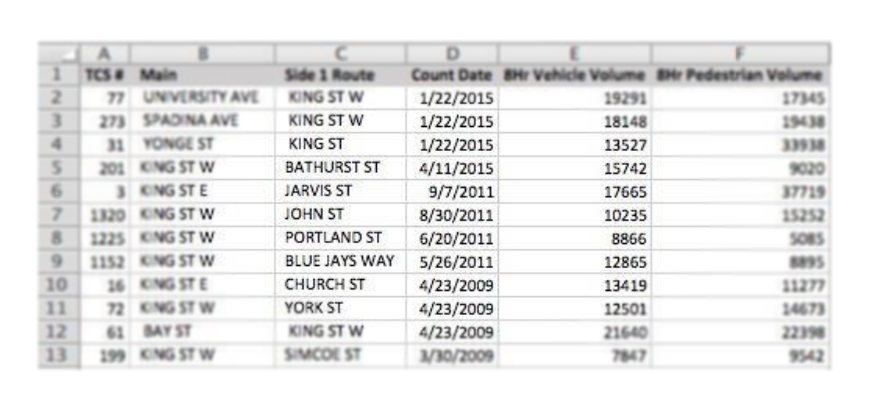

For starters, there are some glaring problems with how and why the TTC launched this project. The optics surrounding 65,000 transit users and 20,000 vehicles are completely deceitful. After looking over data provided by the City and the TTC, it’s clear the methodologies used for both public transit and vehicles are different in how they’re being presented to the public: 65K+ passengers traverse along the entire 14 km stretch of the 504 line, not the pilot zone; 20K vehicles is even more suspicious as the cordon data provided by the City shows a tally of 21K+ vehicles traversing at only one intersection in the pilot zone over an 8 hr window. In short, if you were to tabulate the correct numbers for the same areas and times, the numbers would favor passengers in vehicles, not transit riders. In essence, the City and the TTC are purporting a lie, and the citizens of Toronto are buying into the always divisive narrative of transit riders against the terrorizing, unsustainable automobile—and on that note, it’s been a “success” with some articles touting the project a “triumph”. You almost can’t blame the TTC for trying to mislead the public on an idea that simply diverts traffic for its own ends as a “solution”. Bear in mind, that the TTC is still run like a business, continually referring to their ridership as “customers” while also receiving the majority of their operating funds from the private sector—the daily rider. More importantly, the TTC has been losing tens of millions over the past 4-5 years due to a decrease in overall ridership. This will no longer be the case with the launch of the subway extension on Line 1; however, the project should not have launched based on the pre-pilot cordon data and on the passenger comparison. Moreover, the recent data showing a .4 minute time improvement in the morning and a 2.6 minutes time improvement in the evening is not a win for public transit or traffic as a whole.

Much of the argument or the basis for this project has everything to do with how many and who are impacted. The skewed optics used to convince citizens of the King Street Pilot is nothing short of horrendous in its deception. The numbers are misleading, and perhaps deliberately confusing, helping to usher in a project based on whimsy rather than hard data. Public officials claim an all-day weekday ridership of 65,000 passengers on the 504 King line to 20,000 vehicles; a 65K/20K comparison that illustrates a 3.25 : 1 ratio, an imbalance that unfairly addresses the needs of the transit rider over vehicle passengers. However, the numbers are disingenuous as the 65K is an all-day total for an entire 14 km stretch of road of streetcar passengers “boarding,” while the pilot zone is less than 3 kms long, approximately 20% of the entire 504 route. So, the actual numbers of transit passengers traversing through the pilot zone was never made clear, but what is certain is that it’s nowhere near 65K. According to one 2014 TTC report of passenger “ons and offs” along the 504 King line, approximately 37% did not traverse through the zone and approximately 38% of the 65K ridership did not traverse through the zone all day. The number of transit riders in the zone during peak hours is closer to 20-22K, similar to the vehicle count of 20K. Where’s the 3:1 ratio? Also, it can only be assumed that the 20K figure for vehicles was near the pilot zone since it’s impossible that only 20K vehicles touch all 14 kms of the 504 line “per day”. Furthermore, cordon data provided by the City shows vehicle traffic at King & Bay streets (with a one-day 8hr tally) totaling 21,640 vehicles; this fact immediately disproves the suggestion that only 20K vehicles touch the 504 line, especially the entire 14 km stretch. Furthermore, if one were to apply the same methodology of 65K passengers “boarding”—in other words the “ons”—and apply it to vehicles “boarding” the entire 14 km stretch of King Street, the number could theoretically be twice the total of 65K streetcar passengers if not astronomically higher for an all-day total. Place your bets on it being astronomically higher than 65K. Also, the number of passengers in vehicles was never included in the vehicle totals, so that would have to factor in as well to the mysterious “20K” figure the TTC and the City are purporting. When you factor in 1.2 passengers for the private vehicle count, you have 24K vehicle passengers. That leaves a 24K passenger count for private vehicles and approximately 20-22K 504 King line passengers for peak hours (in any case a ratio more 1:1 if we are to take the “20K” figure by the City as fact); while the comparison outside of peak hours immeasurably favours vehicles over transit. Also, the cordon counts for vehicles were dated, in some cases almost ten years old, so the numbers are conservatively low.

Those who live in the city and take transit assume their travel times are significantly longer than those driving to and from work, but this is speculative. Depending on the source, the numbers differ slightly, but the average commute for a driver is 50+ minutes, whereas the average commute for a transit rider in Toronto is 30+ minutes. The City is essentially prioritizing public transit over any other transport even when the commute times already favor TTC riders. The City is also favoring the TTC as a business over other private businesses along the strip, where a drop in revenue is threatening jobs and squeezing them entirely out of the neighborhood. Traffic is a shared problem, it’s not simply designated to the public transit user, and one cannot rid of vehicles that transfer the elderly, children, goods and services, no matter how exclusive you make your city. If one is not for sharing the roads for all, they’re adopting isolationist views, afraid of the foreign suburban horde of vehicles invading their city. Many suburbanites traverse through the city’s core during the day and night; a grievance to city-dwellers who often feel superior to their non-urban counterparts. It shouldn’t have to be said, but drivers of vehicles have as much right to the road and a reduction in commute times as any other taxpayer. I think many would like to live and raise their families in the city and walk or ride their bike to work if they could afford the cost of living in the city and if condos were designed to accommodate families. There’s a singularity here where those who are for the project do not realize their own blind spot on the topic. Like so many politically heated debates today, people take a side before digesting the facts, siding on blind faith in regards to statistics and taking comfort where the language sounds familiar and breeds familiarity.

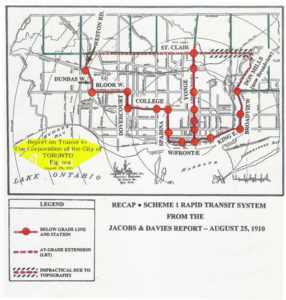

City Officials manage and oversee taxpayer funds in Toronto, but the consequences don’t seem to matter to city planners as they envision “European” ideals to easily transplant themselves to a city that historically has lacked adequate subways and whose population density is expanding aggressively each year without substantial changes to its infrastructure. Take note, that former Chief City Planner, Jennifer Keesmaat—one of the key players in the King Street Pilot—was stunned at the increased demand for transit from the Liberty Village neighborhood, an area that saw significant condo development and an influx of thousands of residents. Why aren’t real issues being discussed regarding development, city planners and officials who were granting developers for the last 15 years to build high-rise condos, who then are surprised by increased congestion from those very same areas? The lack of foresight is inconceivable if not embarrassing. And in that time, no funds were set aside for a municipal coffer towards a Downtown Relief Line (DRL); or funds borrowed to start digging subway tunnels to deal with congestion in an adequate way, for what should have been the expected transit demands for what should have been the foreseeable future of transit demands.

No one is in disagreement about the DRL, and yet it continues to get pushed aside for other transit issues; issues whose “solutions” come at the cost of consultants, barricades, signs, police enforcement, oversized planters, decreased pedestrian traffic and a loss to businesses. Why? The city flirts with plans to build a park over rail tracks with an estimated price tag of 1.7 billion dollars; titled the Rail Deck Park, this legacy project stands in the way of funding greater public transit needs. Yet another fifteen years will have been lost to add to the 100 years of the DRL’s continued shelf life, and it continues to sit as part of the City’s never-to-do, to-do list. Torontonians shouldn’t be celebrating the King Street Pilot, rather they should be ashamed of a patchwork “solution” that only symbolizes the ineptitude of the City in the areas of traffic and transportation services, and ultimately on how the TTC is funded. As someone who is a strong advocate for public transit, I still have to take issue with the deception of the data that launched the pilot and on the very idea itself that the Project would be a solution to congestion in the city. On both of these principles, I felt compelled to address the lies.

More subways would provide relief for above-ground congestion, including cars and public transit. Billions have come to the municipal government through tax dollars with added development and density and it’s time that much of these tax dollars are channeled towards funding subways, rather than simply diverting above-ground problems “elsewhere” with NIMBY-like tones as a solution for traffic congestion. Underpasses could also help relieve congestion at major intersections or key points in the city to keep traffic moving for all. Many businesses have been adversely affected seeing a substantial 20-30% drop in revenue (some as high as 50%) as reported by many news outlets. The former Chief City Planner, Jennifer Keesmaat, and colleagues, swept aside an entire segment of the city taxpayer—the car owner—having bestowed carte blanche enterprise to implement a project that never should have been executed. It is here that a lie was established based on deceptive and misleading data favoring public transit that propelled the project forward, not based on a benefit for all citizens but rather to fulfill dreams of “European” ideals that exist in the minds of a few city planners and a legion of transit riders with a take-all attitude who mistakenly believe Toronto can be London, Amsterdam, or Berlin. And it is here where the narrative of vehicles impeding on the viability for a more transit and pedestrian-friendly corridor takes root. To execute a plan so haphazardly is what often accompanies tyrannical processes, leaving many to suffer the adverse consequences.

But unlike New York, Paris or London—dense, ancient stalwarts who hold a pedigree of established transit networks, with well-funded and well-designed urban planning initiatives—Toronto simply lacks the established qualities and characteristics to forge ahead in similar fashion. Torontonians will often project the idea that it’s a big, sophisticated cosmopolitan city, but the visual that often comes up is a still-teething adult holding adult expectations. Toronto must first admit to itself that it is not any other city, it is Toronto, with Toronto problems, and it must address its problems as Toronto-specific. In this regard, Toronto’s biggest problem is arguably traffic and public transportation, but more specifically, traffic flow is the issue relating to this current project. For some, cars are the cholesterol clogging the arteries of the city, while public transport is the statin to solve all that ails the congestion. Streetcars may be a delight in European cities that possess a population more sparse than dense, and even then, they’re not always a great solution. More cars is said to be an unsustainable idea, however, more density with insufficient public transportation is also unsustainable. There’s also evidence to assume that there will be a decrease in private car ownership in the coming years, as Uber appeals to a generation more likely to travel abroad than it is to save for private vehicles.

The launch of this pilot has now created a narrative where many take sides based on abstract political issues and identity politics rather than the data. This has also provided Councillor Doug Ford with newfound ammunition to attack his opposition, namely Mayor John Tory, as he vies for mayoral candidacy in 2018. Councillor Doug Ford has already seized the opportunity by uploading a video to YouTube showing the congestion issues as a result of the pilot. Bad ideas are the gunpowder needed to fill hollow shells that will inevitably ricochet back into the foray for any aspiring political candidate—especially for politicians void of any good ideas themselves.

Unfortunately, this project is one that shows the inability of a major city to make major problems go away. There is something particularly embarrassing about the King Street Pilot, something that seems uniquely Toronto. Innsbruck has the not-so-bustling population of approximately 130K, a density measure of 1,200/km2 (3,200/sq mi). They can handle all the streetcars they want, alongside bicycle lanes and widened sidewalks to provide idyllic photos for their brochures; but to compare and implement these ideas for some of the densest parts of Toronto is buffoonery. Cities like Berlin, with a population density similar to that of Toronto make use of streetcars, but their extensive, sophisticated subway network complements the streetcar, which then allows for above-ground changes to be adopted with little or no issue. How is it that Jennifer Keesmaat and her colleagues lacked the foresight, urban-planning knowledge and strategic skills to understand this? Perhaps, they felt that a similar project that took place in Melbourne that diverted car thoroughfare in favor of streetcars, which was deemed a success there, could be implemented here. However, with both Toronto and Melbourne holding comparable characteristics, the main ones which do not and which are key to the argument, is that Melbourne’s overall transit network is far more sophisticated and far-reaching; and the density in this corridor is not as dense as that along the King Street Pilot zone, all of which allows for changes like this to occur without significant collateral damage. Melbourne was built around an extensive rail network that makes it possible for radical traffic changes to be made without hiccup. It is absolutely negligent for Toronto to execute projects like this in similar fashion without taking into consideration the unique factors that could make it a disaster.

Perhaps the conversation of transit should shift to confront the real elephant in the room, which is to pivot towards the streetcars themselves. Streetcars cause traffic as much as they get caught in traffic—even for other streetcars. Simple as this seems, it’s a concept that fails to reach those at City Hall. No other city in the world with narrow lanes and density like this (particularly in this stretch) possesses a streetcar track that lacks a thoroughfare for vehicles, unless of course they already have an adequate subway to complement above-ground traffic. Montreal abandoned streetcars decades ago for subways, and with a population density a fraction of Toronto’s, it has positioned itself to deal with public transit issues more adequately for those still willing to take public transit. Also, take note, despite the efficiency and spread of their public transit, it hasn’t forced car owners to abandon their vehicles as Montreal possesses some of Canada’s highest average vehicle commute times. Furthermore, in a city as densely populated as Bogota (a city without subways) public authorities implemented a new public transit initiative that opened in 2000—a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system called the TransMilenio. The TransMilenio saw an increase in buses and routes, but the outcome was surprising in other ways. From 2002 to 2012, car ownership went from 509K cars to 1.29 million; this is at the height of the TransMilenio project. We are led to believe that an increase in public transit will convert or even prevent others from purchasing vehicles. The case in Bogota proves otherwise, but cases in Toronto also prove that an increase in public transit doesn’t necessarily mean an increase in ridership, at least in the long-term. The Spadina ROW streetcar when implemented, did see a significant increase in ridership (approx. 10K) after its launch, but as of recently, that increase has been reduced to its 2005 levels of ridership; astonishing considering how much Toronto has increased its urban density over that time.

To improve public transit is to improve traffic flow, and to improve traffic flow is to improve public transit. For those who see the pilot as putting cars “where they belong” and a win for the “little guy” are failing to consider the long-term affects. By pushing out vehicles or impeding their flow, the project creates barriers both visible and invisible. Jane Jacobs left New York for Toronto as she saw a well-balanced city of neighborhoods built on a human scale, but one that was also inclusive. Currently, the issue of Toronto’s success, is that it’s too successful, with a substantial increase in population putting strains on infrastructure and a cost of living that is prohibitive and restrictive for most, becoming more and more unlivable. The marginalized were able to survive in varying neighborhoods, however, today, many of them, even those with healthy incomes are moving to Hamilton and other outskirts. The rhetoric and the signage that force vehicles to second guess their commute into the city is a barrier, and the message is resounding both as a deterrent and one that can be described as disparaging; meaning if you don’t belong to the older parts of the megacity, you’re not welcome–price of admission is buying real estate in the core, or doubling your commute time by taking limited transit options–thus setting hierarchical markers. Projects like this won’t force drivers into streetcars, drivers will simply take the next easiest option, which, if possible, is to avoid the area completely. The loss to businesses since the launch is proof that drivers would rather go elsewhere than abandon their vehicles in exchange for a smooth ride on transit. The King Street pilot isn’t a balanced solution, and it’s simply bringing on the slow Manhattan-ization of Toronto through gradual atrophy via traffic congestion; making it less desirable to live on the outside if one has to commute to its inside, in turn increasing greater desirability for inner-city living, escalating real estate demand and thus prices inside the core. The same will gradually occur at its periphery to the point where local baristas have to commute an hour or more each way from their more affordable communities at somewhere-and-Alaska to pour lattes to the privileged few who reside inside the expensive “pedestrian-friendly” elite core. The widening of sidewalks will benefit the real estate owners in the area more so than the Parkdale resident who may traverse through the pilot zone every so often. This project is ushering in pedestrian-friendly space for the richest in the city, but thankfully, those in the core are now saving up to 2.6 minutes on their transit ride home.

Ideas like this bring division between classes and makes the situation untenable. The invisible Hudson River moat is slowly being built via ideas that ironically perpetuate to service those less fortunate, on representation of data that was misleading and implemented with capricious fancy. The King Street project is home to some of the wealthiest real estate in the city, along its major entertainment strip including TIFF’s headquarters and its theatre district, home to ever-growing colossal condo projects like the Mirvish/Gehry buildings, and major banking and financial exchange hubs. Take note that this project doesn’t continue further into Parkdale, one of Toronto’s more neglected neighborhoods, where peak times also see a large cluster of vehicles congesting King Street. If the purpose is to increase travel time and ridership, then that principle would have to extend the entire 504 line, rather than simply imposing a stretch that is less than 3 kms long. However, any proposal that is based on misleading the public and misrepresenting data to push an agenda, ultimately illustrates an abuse of power. If the project needn’t be sold to the public because of how inherently great it is, then why the lack of clarity in the pre-pilot numbers? The project has to be exposed as being launched on a lie and therefore abolished, and the mainstream media cannot continue to perpetuate that a .4 – 2.6 minutes reduction in commute times is a success. Any possible increase in ridership or a decrease in commute times distracts from the truth or the theoretical inverse of such a project: what would the commute times and the vehicle counts be if streetcar thoroughfare was banned? Obstinance from the City only suggests that either the culture surrounding public transit is completely and willfully misinformed, or that they’re aware of the misleading numbers and are choosing to ignore them for single-minded, dogmatic and ideological reasons. Either way, transparency is all the citizens of Toronto should be concerned with if they expect their municipality to function with integrity, if nothing else.